FBAR – Form 114 Foreign Account Reporting

I have foreign financial accounts; Do I need to report them?

Yes, whether you live in the U.S. or abroad, if you have financial interest in or signature authority over foreign financial accounts, you are required to disclose them. If it’s a small sum of money, disclosure may mean simply checking a box on your tax return. For a larger sum, you may be required to disclose them to the Treasury Department annually through an FBAR filing.

What is an FBAR?

FBAR refers to IRS Form 114, the Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts Report. It is a separate and independent filing from your normal income tax return. It’s an information-only form, meaning that no tax will be due because of the information supplied on an FBAR.

Do I have to file an FBAR?

The IRS states: U.S. persons are required to file an FBAR if:

- The U.S. person had a financial interest in or signature authority over at least one financial account located outside the U.S.; and

- The aggregate value of all foreign financial accounts exceeded $10,000 at any time during the calendar year reported.

They go on to define a U.S. person broadly as including:

- U.S. citizens;

- U.S. residents;

- entities, including but not limited to, corporations, partnerships, or limited liability companies, created or organized in the U.S. or under the laws of the U.S.; and

- trusts or estates formed under the laws of the U.S.

Basically, if you have a connection to the U.S. and you have a foreign account with some monies in it, there’s a high likelihood that you are required to disclose it on an FBAR.

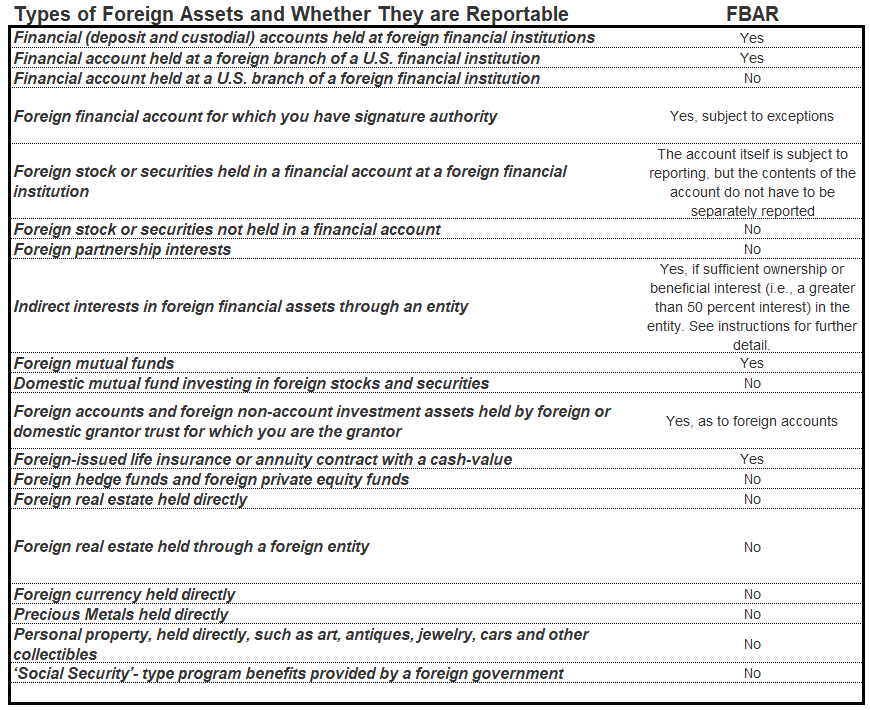

What type of accounts need to be reported on an FBAR?

All foreign financial accounts which you own wholly, jointly, or you have signature authority over must be reported. Foreign financial accounts include, but are not limited to:

- Checking

- Savings

- Securities

- Investments

- Brokerages

- Annuities

- Deposit Accounts

- CDs

- Any other monetary account that is held with a foreign institution

The IRS provides this nifty chart to help:

Have I exceeded the $10,000 threshold for the FBAR filing requirement?

The $10,000 threshold is based on “the aggregate value of all foreign financial accounts… at any time during the calendar year”.

It’s not as simple as looking at the value of your foreign accounts on December 31st and adding them together. You must:

- Determine the maximum value of each account in local currency during the year.

- Convert each maximum value into U.S. dollars using the official U.S. Treasury exchange rate at the end of the year. (Which can be found here: Official Historical Exchange Rates)

Let’s do an example: You are living in Greece and maintain a local checking and savings account, between which you typically move money to pay your bills. You’ve only ever had €8,000 total between the two accounts, but individually each had a highest balance of €6,000 during the year. Upon first look, you may not think that you have a FBAR filing requirement, but transfers between multiple foreign accounts can cause the same funds to be counted twice and push you over the threshold.

To determine if you have crossed the $10,000 reporting threshold you would aggregate the €6,000 highest balance of each account during the year to get €12,000. Then you would convert €12,000 to U.S. dollars using the year-end Treasury exchange rate (we’ll use 1.2 dollars to euros), giving you a total of $14,400, well above the filing requirement.

In the above example, you have an FBAR filing requirement based on $14,400, even though at no time during the year did your total foreign assets exceed €8,000 ($9,600). It’s your transferring funds between accounts that pushed you over the threshold. This leads to the question:

Should I avoid transferring funds between foreign accounts and double counting assets?

Potentially, if you’re able to stay below the $10,000 threshold for FBAR reporting and therefore avoid the additional filing requirement. However, for taxpayers close to the threshold or well above it, avoiding transfers would be an unnecessary inconvenience.

Remember, FBAR is an information-only form. If you’re doing a lot of transfers, your account values will look a little bigger and you may appear a little richer, but this won’t cause you to pay a penalty or owe additional taxes. This is the proper way to complete the form.

To say it another way, you won’t owe additional taxes simply for having a foreign bank account or filing an FBAR. Of course, if your foreign bank account pays interest, dividends, or is invested, you may owe taxes on that income. That information must be reported on your income tax return, just as it would be if it was a U.S.-based financial institution.

What is the due date for FBAR filing?

Although your FBAR is filed separately from your annual income tax return, the due date is the same and the two should be coordinated. If you are living in the U.S., the due date is April 15 (usually) . If you are living outside the U.S. on the normal filing deadline, you’ll receive an automatic extension to June 15, which applies to your income tax return as well as your FBAR filing. Note that FINCEN, the agency that oversees FBAR filing, stated that taxpayers failing to meet the FBAR annual due date of April 15 are granted an automatic extension to October 15.

How do you file an FBAR?

FBARs must be filed electronically through the BSA E-Filing System. If you are preparing your own FBAR, you should create an account. If you’re working with a CPA or paid tax preparer for your income tax return, they can file your FBAR as well.

Your FBAR and income tax return should be coordinated. On Schedule B of your income tax return you should notify the IRS that you’ll be filing an FBAR and list in which countries you hold or have signature authority over foreign financial accounts.

Should I open a foreign bank account?

This is a complicated question! The answer depends a lot on non-FBAR related details. Don’t let the FBAR filing requirement stop you from opening a foreign bank account for legitimate purposes that will make your life easier. Yes, your tax return will become a bit more complicated, but a qualified CPA or tax preparer should easily be able to handle your FBAR filing.

Why should I care about FBAR reporting?

Well, it’s your duty as a patriotic American! If that didn’t do it for you, maybe penalties will do the trick… and when it comes to the FBAR, the penalties are steep. The IRS breaks them into two main categories: non-willful and willful.

Non-willful: If you are just learning about your FBAR filing requirements (from this excellent blog post), you may be considered non-willful (or, negligent) for past violations of the FBAR filing requirement. This still comes with a penalty of up to $10,000 (for each account you fail to report), but if you can prove there was reasonable cause for failing to file, you may be able to avoid the penalty. Proving reasonable cause can be as simple as stating that you relied on bad advice from a professional or were unaware of the filing requirement.

Willful: If you knew about your FBAR filing requirement and still decide not to file, the IRS is likely to consider you a willful violator and criminal. The penalties for this type of violation get astronomical pretty quickly. We’re talking the greater of $100,000 or 50% of the account value (again on a per account basis, per year).

I didn’t File My FBAR Properly in the Past, What Should I do?

Become compliant! To claim reasonable cause and avoid penalties, you should have documented proof that you’ve taken steps to become compliant before the IRS asks any questions.

Do you have questions about your FBAR filing requirement? Leave them in the comments below!

Resources and Tax Forms:

Tax Guide for U.S. Citizens and Resident Aliens Abroad

IRS FBAR Reference Guide: FBAR

BSA: FBAR E-Filing System